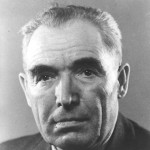

Democratic Socialist and Journalist in Sweden

In 1940, after the occupation of Norway by Hitler’s Wehrmacht, Willy Brandt flees to Sweden, which remains neutral during World War II. There he receives a Norwegian passport and becomes the director of a press office in Stockholm. In addition, Brandt writes books about the war and the period afterward. A free Norway and a different, democratic Germany are his principal goals. He discusses ideas for a peaceful future in Europe and the world in an international circle of democratic socialists. In 1944, he joins the SPD again. In autumn 1945, after the end of the war, Brandt comes to Germany to report as a journalist on the war crimes trials in Nuremberg.

New relationship and new residence

After Gertrud Meyer’s emigration to the USA in May 1939, Willy Brandt does not remain alone for long in Oslo. He becomes reacquainted with the cultural scientist Carlota Thorkildsen, nine years his senior, whom he has known since 1935 during his student days and from meetings of “Mot Dag.” In 1939, the two fall in love and are soon living together in an apartment near the university library in Oslo.

Emigration to England or the USA?

At Jacob Walcher’s behest, Willy Brandt has been trying for several months from Oslo to hold together the widely strewn remains of the SAPD. Since the outbreak of war in September 1939, the SAPD leadership in Paris has had to discontinue its work. Since then all political refugees in France have been detained.

Expecting that Brandt will soon receive Norwegian citizenship, Walcher has advised his young friend as early as late 1939 to leave Scandinavia quickly and immigrate to London. But his naturalisation continues to be delayed. In early March 1940, Brandt writes to Walcher that he would also in principle be willing to move to the USA. Then, of course, he fears no longer being able to return to Europe.

German occupation of Norway

On the morning of 9 April 1940, Willy Brandt learns that German ships have entered the Oslofjord and Wehrmacht soldiers have debarked. At the same time, Denmark is occupied by German troops.

Brandt and his pregnant partner Carlota Thorkildsen immediately leave their apartment and take refuge with a Norwegian couple they befriended. There they decide that Carlota shall remain in Oslo. Outside the city, Brandt meets with Martin Tranmæl and other leading members of the Norwegian Workers’ Party. They travel northward to Hamar by car then further eastward through Elverum to Nybergsund by truck, where they arrive on the morning of 10 April 1940.

Fleeing through Norway

In Nybergsund in mid-April 1940, Willy Brandt finds a few days of sanctuary in a cottage. Then he advances by way of Hamar to Lillehammer. From there he travels further north, by car, with colleagues from the Norwegian People’s Aid Committee. Since British troops, which have landed in the meantime, cannot halt the German advance, Brandt relocates to the west coast. Passing by the small town of Åndalsnes, he makes it to the Langfjord.

Meanwhile, the Germans’ means of pursuit are not immediately operational. Files concerning Hitler’s opponents living in Norway go down with the warship “Blücher.” Of course, the Gestapo immediately destroys Brandt’s freshly printed first book “Stormaktenes krigsmål og det nye Europa” (“The Military Objectives of the Major Powers and the New Europe”).

Imprisoned by the Wehrmacht

During his escape in early May 1940, Willy Brandt is stranded at Langfjord between sea and snow-covered mountains. The Germans have cordoned off the area, and the British have capitulated in southern Norway. By chance he stumbles upon Norwegian volunteers in Mittetal. Among them is his friend Paul René Gauguin, a grandson of the French painter.

So as not to fall into the hands of the Gestapo, Gauguin advises him to put on a Norwegian uniform and let himself be taken prisoner with other Norwegians. Thus Brandt spends four weeks unrecognised as a prisoner of war at a camp in Dovre in the Gudbrandsdal. The 26-year-old is released in mid-June 1940. He finds accommodations with friends in a suburb of Oslo and reunites with his partner, Carlota Thorkildsen.

Escape to Sweden

After his release from the prisoner of war camp, Willy Brandt only remains in Oslo for a short time. To remain undiscovered, he moves for a week and a half to an isolated summer house in Nærnes on the Oslofjord. Here he makes the decision to escape into neutral Sweden.

Brandt departs on the morning of 30 June 1940. First he takes a ferry to Oslo to recover documents, money and clothes from a hiding place. Afterward he travels by train toward the Swedish border. The 26-year-old covers the final kilometres on foot. After a brief stopover at Bolstad Manor, that evening a farmworker shows him a secret pathway across the border. At about one a.m. on 1 July 1940, Brandt turns himself in at the guard post of a Swedish military station near Skillingmark.

In police custody in Sweden

After crossing the border into Sweden on 1 July 1940, Willy Brandt is brought to the police in Charlottenberg where he, as a stateless person, is interrogated. Because he gives political motives for having fled Norway and expresses the wish to immigrate to the USA, Brandt is not deported. A few days later, he arrives at the Baggå refugee camp in central Sweden.

Thanks to the sponsorship of the Swedish parliamentary representative, August Spångberg, whom he has known since his 1937 sojourn in Spain, Brandt is allowed to leave the camp on 22 July 1940. He hopes to finally obtain citizenship at the Norwegian embassy in Stockholm.

1 August 1940

On 1 August 1940, the Norwegian embassy in Stockholm confers Norwegian citizenship on Willy Brandt based on telegraphed instructions from its exiled government in London. He receives a letter of citizenship and a passport valid for two years issued in his birth name, “Herbert Ernst Karl Frahm.”

To a considerable degree, he owes his naturalisation to the support of his Norwegian friends, Halvard Lange and Martin Tranmæl. Since the London office in exile of the Norwegian Workers’ Party requisitions him as an aide, Brandt does not have to return to the refugee camp. He can live freely in Stockholm and takes up residence in the Castor Guesthouse on Kammakargatan 66. Beginning on 1 October 1940, Swedish authorities grant the new Norwegian citizen six months right of residence.

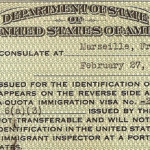

Efforts for a visa to the USA

In New York, Gertrud Meyer has learned of Willy Brandt’s arrival in Sweden from Irmgard and August Enderle, SAPD members living in Stockholm. In late September she informs the couple that she has submitted sureties to US officials for the Enderles and Brandt. Those are requirements for initiating entry visas to the USA, which Meyer works for tirelessly.

In this way she helps several SAPD comrades escape safely because the occupation of vast portions of Europe by Hitler’s Germany has put them in a most difficult position. One of the more significant among them is Jacob Walcher, who escapes to the USA from France by way of Spain. Despite all of Meyer’s efforts, Brandt, the Enderles and other friends from Stockholm do not receive visas.

Birth of his daughter Ninja

On 30 October 1940, Willy Brandt’s first child, his daughter Ninja, is born. However, the new father is separated by more than 400 kilometres from his family, because the mother, Carlota Thorkildsen, has stayed in Oslo. Brandt does not see the baby for the first time until two months later during a secret visit to the Norwegian capital.

Registration as a foreign journalist

Beginning in autumn 1940, Willy Brandt is officially working as a correspondent for New York’s “Overseas News Agency” (ONA). Because of that he is able to register on 11 December 1940 with Swedish authorities as a foreign journalist and to receive a press pass.

For his work as a correspondent, Brandt initially receives a monthly salary of 150 kronor from the ONA and later, in 1941, even 250 Swedish kronor per month. The permanent position helps him considerably in extending his residence permit, since he is not dependent on government support.

Perilous visit in Oslo

Shortly before Christmas 1940, with financial support from the Norwegian Workers’ Party DNA, Willy Brandt travels from Stockholm to Norway to get an impression of the situation in the German-occupied country. A Swedish military patrol takes him and his companion, Inge Scheflo, secretly across the green border. Then the two travel by train to Oslo where they find accommodations in a one-room apartment.

Brandt visits his partner, Carlota Thorkildsen, and sees his daughter, Ninja, for the first time. In addition, at a secret meeting he consults with the former mayor of Oslo and later prime minister, Einar Gerhardsen, who is directing the resistance activities of Norwegian trade unions. On 3 January 1941, Brandt returns to Sweden.

Exchange of letters with Walcher in the USA

In the meanwhile, since its members have been scattered across half the world, the SAPD no longer has a firm foundation. Even the approximately 20 comrades who, like Willy Brandt, have found asylum in Stockholm, are not organised as an official SAPD cell. However, despite irregular postal contacts during the war, Brandt tries to remain in contact with party friends abroad.

In particular, his correspondents include Jacob Walcher, who arrived in the USA in early 1941 after his escape from France and Spain. By that time, Brandt no longer seems to be in such a hurry to immigrate to America himself. On 9 February 1941, he writes to Walcher that he could “perform useful work to an ever-increasing degree” in Sweden to aid Norway’s struggle for freedom.

Arrest by Swedish police

On 28 March 1941, Willy Brandt goes to the Aliens Department in Stockholm to have his residence permit extended. There he is interrogated for hours by officials and finally arrested on suspicion of “intelligence activities for a belligerent power.”

Brandt’s absence during Christmas and New Year’s 1940 has not remained unknown to the SÄPO, the Swedish Security Police. They have been shadowing him and opening his letters since his return from Norway. Brandt admits to the sojourn in the neighbouring country, but remains silent regarding his contacts with the Norwegian resistance movement. While he is under arrest, the police search his apartment and seize five file folders of correspondence. An interrogating official even threatens him with deportation to Germany. But a Norwegian diplomat and Martin Tranmæl successfully lobby for the 27-year-old at various Swedish government agencies.

After six days, Brandt is released, but is admonished to leave Sweden as soon as possible. Subsequently, he remains in the SÄPO’s sights, which observes his activities and secretly checks on his mail. Even though his residence permit in Sweden is extended six times until the end of the war, Brandt is not completely free to move around the country. In all those years he needs a permit for each trip outside Stockholm, whether it be to lectures or to a vacation destination.

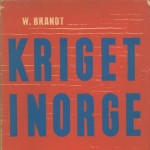

Successful journalist and author

Willy Brandt is a highly diligent political publicist. As a journalist, he writes for a workers’ newspaper, takes on assignments for the Stockholm office of exiles of the Norwegian Workers’ Party DNA and has been a correspondent of New York’s “Overseas News Agency” (ONA) since autumn 1940.

In spring 1941, his book “Kriget i Norge” (“War in Norway”) is published. In it Brandt describes the battles during the occupation of Norway by the Wehrmacht in 1940. The work receives enthusiastic critical appraisal in Sweden and also appears in a 1942 German translation issued by a Zurich publishing house. In addition, Brandt pens further books, brochures and articles about the Norwegians’ struggle for freedom, the war in Europe and plans for the era afterward.

First marriage

In mid-May 1941, Willy Brandt’s Norwegian partner, Carlota Thorkildsen and their daughter Ninja, finally make it to Stockholm. On 28 May, Willy and Carlota marry at the civil registry office in the district of Enskede.

Frahm is the official family name in which Brandt’s Norwegian passport is issued. Carlota has to become accustomed to it, as she has never previously associated her husband with this name. The young family moves into an apartment in the idyllic suburb Hammarbyhöjden where many Norwegian refugees live. Their address is Thunbergsgatan 23.

New plans for America

Due to his negative experiences with Swedish police in spring 1941, which demands his prompt emigration, Willy Brandt plans to immigrate to America with wife Carlota, and daughter Ninja as soon as possible. Therefore, he asks his friend Finn Moe, who is now the press attaché at the Norwegian embassy in the USA, to procure visas for him and his family.

After the German attack on the Soviet Union on 21 June 1941, this seems even more pressing, since the fear is that the Wehrmacht could also occupy neutral Sweden. Brandt and other SAPD friends in Stockholm will not definitively abandon plans to immigrate to the USA until spring 1942.

Group of Norwegian socialists

In Stockholm, Willy Brandt belongs to a “Study group of Norwegian socialists,” which has been discussing internal and foreign policy plans for the post-war period since autumn 1941. Martin Tranmæl is the founder of the group. Brandt receives the assignment to formulate a common position paper.

In late 1941, the 28-year-old speaks out in a letter to Arne Ording, the consultant to the Norwegian foreign minister in exile in London, against a peace treaty of subjugation. Indeed, Germany bears most of the responsibility for the war, but does not bear that guilt alone. Furthermore, not all Germans are Nazis. Brandt emphasises that the people’s right of self-determination must apply as well to a democratic Germany which will be expected to contribute to the reconstruction of Europe.

Family life in Sweden

In early 1942, Willy Brandt moves with his wife, Carlota, and daughter, Ninja, into an apartment in a new building. At the time, the address in Hammarbyhöjden, a suburb of Stockholm, is Finn Malmgrens Väg 23.

Together the couple provides for their livelihood. Brandt works as a journalist, Carlota in the press office of the Norwegian embassy. For the situation at the time, the family lives comparatively well. They can afford an annual ski holiday and summer vacations, which sparks the envy of other emigrants. But soon thereafter the young marriage starts to show signs of a crisis.

Peace-time goals of Norwegian socialists

In late May 1942, after six months of consultations, the Stockholm “Study group of Norwegian socialists” under the direction of Martin Tranmæl completes its paper “Diskusjonsgrunnlag om våre fredsmål” (“Fundamentals for discussion of our peace-time goals”). The 19-page document which the group publishes a short time later and discusses in early July 1942 with Swedish and foreign socialists, was written for the most part by Willy Brandt.

Based on the expectation that the “Third Reich” will lose the war, the paper calls for the eradication of Nazism and militarism in Germany, reparations for injustices committed by the Germans as well as the punishment of those responsible for the war and its crimes. However, the paper further states, Germany shall not be partitioned and its economy not permitted to collapse. The allied powers must also not hinder the German people from carrying out a socialist revolution, but rather must support German democrats.

The proposals, however, encounter fierce criticism within the London-based Norwegian exile government, with whose foreign policy adviser, Arne Ording, Willy Brandt has been exchanging letters. They are categorised as too lenient toward the Germans.

Resistance newspaper “Håndslag”

On 1 June 1942, the first edition of the newspaper “Håndslag – Fakta og Orientering for Nordmenn” (“Handshake – Facts and Orientation for Norwegians”) appears in Stockholm. The editor is the Swedish writer Eyvind Johnson.

His most important associates are the editors Willy Brandt and Torolf Elster. Every two weeks, until June 1945, they inform their readers about the situation in occupied Norway and the progress of the war in Europe. “Håndslag” reaches not only exile Norwegians but also many compatriots in the homeland where the paper is distributed by the underground resistance.

In mid-June 1942, Brandt publishes another book in Stockholm’s Bonniers Publishing Company with the title “Guerrilla War.” In it he describes the history of conducting small-scale warfare since the early 19th century.

The opening of a press agency

Commissioned and supported by the Norwegian Embassy, Willy Brandt and the Swedish journalist Olov Jansson open the “Svensk-Norsk Pressbyrå” (“Swedish-Norwegian Press Bureau”) in Stockholm on 31 July 1942. Jansson is formally the owner, but Brandt is the executive editor. Another associate is the Swede Einar Stråhle.

The bureau headquartered in Vasagatan 37 provides the latest news about occupied Norway and is subscribed to by ca. 70 Swedish daily newspapers of the most varied political leanings, by several embassies as well as by foreign journalists and agencies. Until the end of the war, Brandt publishes under the name “Karl Frahm” more than 5,000 articles, many of which he also uses for the resistance newspaper “Håndslag.”

“Little International” in Stockholm

In September 1942, an “International group of democratic socialists” meets in Stockholm for the first time to discuss the post-war order in Europe. It succeeds the “Study group of Norwegian socialists.” From the very beginning, Willy Brandt plays a key role. In autumn 1942 he becomes the secretary of a committee charged with working out an outline for the peacetime goals of the group.

Until 1945, ca. 60 democratic socialists from 14 countries regularly take part in the assemblies of the so-called “Little International.” Members of the inner circle are, among others: Martin Tranmæl, the Austrian Bruno Kreisky, the Swedes Torsten Nilsson as well as Alva and Gunnar Myrdal, the Hungarians Vilmos Böhm and Stefan Szende, the Pole Maurycy Karniol and the Germans Ernst Paul and Fritz Tarnow.

Initial reports about the Holocaust

Willy Brandt also writes about the persecution of Jews in the regions occupied by the Germans for New York’s “Overseas News Agency” (ONA). In January 1943 he reports for the first time that the NS regime is gassing Jews. The ONA correspondent obtained this terrible news from the Pole Maurycy Karniol, who is associated with the “Little International” in Stockholm.

Although the American press agency distributes Brandt’s report, only a few newspapers in the USA reprint it. The ONA chief at that time, Hyman Wishengrad, later maintains that this article was the first indication of the existence of death camps. However, the true extent of mass murder against European Jews, which the Germans have been committing with unimaginable cruelty since 1942, is not yet known to Brandt.

Additional books about Norway

In spring 1943 in Stockholm’s Bonniers Publishing Company, a new book by Willy Brandt appears under the title “Norges tredje krigsår” (“Norway’s Third Year of War”). It describes the oppression of the Norwegian people by their German occupiers and the activities of the resistance against them. Brandt wrote the manuscript in Norwegian. Olov Jansson translates the text into Swedish for the print version.

The military defeats of the Germans in North Africa and in Stalingrad in 1942/43 encourage Brandt’s optimism. Next to his daily work as a journalist, he also publishes numerous brochures and books devoted to the Norwegians’ struggle for freedom. Thus the volume “Norge: ockuperat och fritt” (“Norway – occupied and free”) appears in 1943.

“Little International”: peacetime goals

On 1 May 1943, over 500 Swedish social democrats and 100 democratic socialists from 13 countries come together for a rally in Stockholm. Willy Brandt delivers the keynote speech and as secretary of the “International group of democratic socialists,” presents its peacetime goals. The Resolution, passed in March 1943, had been formulated for the most part by him.

In it, the “Little International” advocates the right of all nations to self-determination, which should also be applicable to a democratic Germany. It calls furthermore for democratisation of states and societies, the unification of Europe, the end of colonial rule and the creation of the United Nations. Most important of all, these suggestions harken back to the Anglo-American Atlantic Charta of 1941.

Against communist defamation

Willy Brandt’s book, “Norges tredje krigsår,” creates a stir. The communist newspaper in Sweden, “Ny dag,” reacts to its criticism of the Norwegian Communist Party with vicious personal attacks. They accuse Brandt of being a German and having betrayed Norwegians to the Gestapo.

In an “Open Letter to the Communists”, which appears in August 1943 in the newspaper “Trots allt,” the 29-year-old decisively refutes those slanders. He has never denied and is not at all ashamed to be a native-born German. Brandt stresses: “I feel bound to Norway with a thousand ties, but I have never given up on Germany – the other Germany. (…) I am working to win back two fatherlands – a free Norway and a democratic Germany.”

Intelligence agent?

In September 1943, Willy Brandt writes a paper about the anti-fascist forces in Germany. In it he evaluates, quite soberly, the prospects for the German resistance against Hitler’s regime: The opposition will only emerge seriously when the military defeat of the “Third Reich” is certain beyond a doubt. This analysis reaches the headquarters of the American intelligence service, the Office of Strategic Studies (OSS) in Washington.

Based on this and other reports, later the erroneous assertion is made that Brandt had been an agent or spy for foreign powers during the war. For his part as a journalist and Nazi opponent, it is a matter of course, however, to maintain contacts with representatives of the anti-Hitler coalition. The information and news that Brandt obtains are used for his articles and books. In return, he passes on his own knowledge about the situation in Norway, Sweden and Germany to American, British and Soviet representatives.

It was supposedly known to him that his interlocutors in Stockholm were also working for the intelligence services of their respective countries and passed Brandt’s reports on to them. Aside from the exchange of information, with the help of these contacts, Willy Brandt is also interested in having an influence on the allies’ plans for Germany in the post-war era.

Contacts with the German resistance

In winter 1943/44 in Stockholm, Willy Brandt is introduced by an acquainted businessman to the German lieutenant colonel Theodor Steltzer. In Norway, Steltzer organises the Wehrmacht’s transportation facilities and is a conservative opponent of the Nazi regime. He indicates to Brandt that there is a secret group of military men and politicians in Germany who intend to remove Hitler from power.

One member of this later so-called “Kreisauer Kreis” (“Kreisau Circle”) is the social democrat Julius Leber, with whom Steltzer, by his own admission, is well acquainted. Brandt is very happy to learn something about his former sponsor in Lübeck and sends him greetings. During the next few months further meetings take place with Steltzer who also speaks in Stockholm with the trade unionist Fritz Tarnow.

Love affair with Rut Bergaust

At the beginning of 1944, Willy Brandt is badly weakened as a result of yellow jaundice. He had to spend his 30th birthday on 18 December 1943 in bed with a high fever. Even weeks afterward he is hardly able to work and frequently stays at home.

During this time he and Rut Bergaust fall in love. The 23-year-old Norwegian woman helps in the household of Willy and his wife Carlota and cares for their young daughter Ninja during the day. The new love affair, which neither of them can keep secret by summer 1944, results in serious conflicts. Neither Carlota nor Rut’s husband will agree to a divorce. Furthermore, Rut’s husband Ole Bergaust falls gravely ill soon afterwards. Things fluctuate for months. Willy’s separation from Carlota is not a certainty until the turn of 1944/45 when she and Ninja leave their apartment in Hammarbyhöjden.

Public appearances in Sweden

The more likely the military defeat of Germany becomes, the more freely refugees in neutral Sweden are able to be politically active. Since May 1943, Willy Brandt has even been able to make appearances at public assemblies. For example, in February 1944, he delivers a lecture to the “Samfundet Nordens Frihet” (“Association for the Freedom of the Nordic Countries”), a liberal-democratic club representing anti-Nazi and anti-communist viewpoints. The theme of his address is “Co-operation in War and Peace.”

The 30-year-old maintains very close contacts with Sweden’s social democrats. At the May Day rally in Stockholm, a Swedish newsreel crew happens to take the first film footage of Willy Brandt as he takes part in the demonstration march along with his wife and daughter.

“Efter Segern” (“After Victory”)

On 3 May 1944, another book by Willy Brandt appears in Stockholm’s Bonniers Publishing Company titled “Efter Segern” (“After Victory”). The work in the Swedish language has an initial printing of 2,200 copies. The Norwegian manuscript was translated by his colleague in the Swedish-Norwegian Press Bureau, Olov Jansson.

Like his friends in the “Little International,” Brandt assumes that the anti-Hitler coalition will be victorious and also continue its co-operation after the war. However, the 30-year-old vigorously opposes demands for severe punishment of Germany by the victorious powers USA, Great Britain and the Soviet Union. With reference to the “other Germany” of German democrats, Brandt emphasises that not all Germans are Nazis and criminals.

Contacts to would-be Hitler assassins

On 24 June 1944, Willy Brandt receives a surprise visit from a Swedish acquaintance who brings along a guest. It is the German legation councillor, Adam von Trott zu Solz, who belongs to the resistance group “Kreisauer Kreis” (“Kreisau Circle”). The diplomat brings greetings from Julius Leber and requests his trust.

Without revealing the names of the conspirators, Trott informs him that the removal of Hitler is planned for some time in the following weeks. Without hesitation, Brandt replies with “Yes” to the question if he would be available to serve a new government and take on an assignment for it in Scandinavia. Two days later he meets with Trott again for further discussions. However, the attempted assassination of Hitler, which takes place on 20 July 1944, fails.

On the post-war policies of German socialists

In July 1944, 18 former functionaries of the SAPD living in exile in Sweden publish the brochure “Zur Nachkriegspolitik der deutschen Sozialisten” (“On the post-war policies of German socialists”). The principal authors are Willy Brandt, Stefan Szende as well as Irmgard and August Enderle. The work discusses the prerequisites for a democratic revolution in Germany and the foreign-policy framework for a new German democracy.

For German socialists, the most important peacetime goals are a democratic and undivided Germany, a framework for peace in Europe and a new league of nations. With a view to Germany’s eastern border, Brandt can imagine ceding East Prussia and Danzig to Poland. But he emphatically rejects a relocation of up to nine million Germans to the west.

Re-admission to the SPD

On 9 October 1944, 14 former SAPD members, among them Willy Brandt, apply together for admission to the Stockholm group of the SPD in exile (Sopade). In a declaration, they give as reasons for this move a desire to overcome the earlier splintering of the workers’ movement in Germany and to initiate the creation of a socialist-democratic party of unity. As revealed in one of his letters to Jacob Walcher, Brandt is sceptical about the communists participating in such a party of unity.

On 18 October 1944, the Stockholm local group of the SPD admits the former SAPD members. Kurt Heinig, who represents the London party executive committee in Sweden and who has a deep aversion for Willy Brandt, unsuccessfully attempts to prevent the move.

Founding of the journal “Socialist Tribune”

n January 1945 in Stockholm, the monthly journal “Socialist Tribune” appears for the first time. It is published by the national group of the SPD in exile in Sweden. Along with Fritz Bauer, the later attorney general of Hesse, Willy Brandt developed the concept for the publication in late 1944.

The “Socialist Tribune” quickly becomes the leading press organ of German-speaking exiles in Sweden. At first, Bauer is editorial director. In summer 1945, Brandt becomes his successor.

On Germany’s future foreign policy

While the Big Three, Franklin D. Roosevelt, Winston Churchill and Josef Stalin, negotiate the post-war framework for Europe, Willy Brandt delivers a lecture on 9 February 1945 before members of the Stockholm local group of the SPD in exile on the subject “Germany’s foreign-policy position after the war.”

The 31-year-old stresses the following: “Unconditional acknowledgement of the crimes that were committed against other peoples by Germans and in the name of Germany is the first precondition for a recovery of the German people.” Brandt continues that a democratic Germany must provide reparations to countries desolated by the war, and quite especially to European Jews. It cannot choose between East and West but must work together with all nations.

Liberation and end of WW II in Europe

On the evening of 1 May 1945, the “International group of democratic socialists” (“Little International”) meets in Stockholm. During his speech at the conclusion of May Day celebrations, Willy Brandt is handed a slip of paper which he immediately reads aloud: “Adolf Hitler is dead.”

On 8 May 1945, Germany surrenders unconditionally. With that the Second World War in Europe is over, and the countries occupied by the Germans are free again. A few days later, Brandt travels by train to Oslo to report on liberated Norway for the Swedish press. He stays in the “Pensjon Themis” at Pilestredet 15 B and remains for three weeks in the Norwegian capital, which is in a delirium of joy. In the following months, the journalist commutes several times between Stockholm and Oslo.

Potsdam Conference of the Big Three

At Cecilienhof Palace in Potsdam, the heads of government of the USA, the Soviet Union and Great Britain – Harry S. Truman, Josef Stalin and Winston Churchill (later, Clement Attlee) – discuss, from 17 July to 2 August 1945, the future of defeated Germany. In the later so-called “Potsdam Accord” they formulate four main goals for a unified allied policy of occupation: denazification, demilitarisation, democratisation and decentralisation.

In addition, the big three decide to allocate to France an occupation zone in the southwest of Germany and a sector in the Reich’s capital city. As the fourth victorious power, France receives a seat and vote on the Allied Control Council and at Allied Headquarters in Berlin.

Criticism of Potsdam border arrangement

In an article for the journal “Socialist Tribune,” published in Stockholm in September 1945, Willy Brandt states his position on the agreements at the Potsdam Conference. There the victorious powers, the USA, Great Britain and the Soviet Union enunciated a month previously their decisions for the preservation of the political and economic unity of Germany on the basis of the borders of 1937. But until the conclusion of a peace treaty, the territories east of the Oder and Neisse rivers have been placed under Polish administration.

Basically, Willy Brandt evaluates the Potsdam Accord as progress. He sees the co-operation of the victorious powers and the improved co-ordination of their occupation policies as a requirement for the democratic reconstruction of Germany. To the contrary, however, the 31-year-old considers the arrangement for the eastern border of Germany to be “unreasonable.” Possibly though, nothing about it can be changed. All the same, Brandt declares that German democrats should not merely agree to the arrangement, but rather work for appropriate modifications in a peace treaty.

He adamantly rejects the expulsion of Germans living in the East which has been underway since the end of the war. According to the decision by the Big Three in Potsdam, the “transfer” of the German population from Poland, Czechoslovakia and Hungary to the West is supposed to “occur in an orderly and humane manner.” In reality, ca. 12 million Germans are expelled by force or compelled to flee their homelands.

Return to Germany

On 8 November 1945, Willy Brandt steps into a British military plane in Oslo. He is on his way to the Allies’ trials in Nuremberg against the major war criminals of the “Third Reich.” After stopovers in Stockholm and Copenhagen, the 31-year-old arrives the following day in Bremen.

He steps on German soil again for the first time since 1936. Bremen’s mayor, Wilhelm Kaisen, lends him his staff car with chauffeur, so that Brandt can visit his mother in Lübeck. In downtown Lübeck, which lies in ruins, the returnee loses his orientation. Brandt has to ask for directions to the address Ringdienstweg 21, where Martha Kuhlmann and her family have been living since 1937. His mother is very happy when she sees her oldest son again on the evening of 11 November 1945.

Observer at the Nuremberg trials

On 20 November 1945, the trial against the major war criminals of the “Third Reich,” among them Hermann Göring and Albert Speer, begin before the International Military Tribunal in Nuremberg. Willy Brandt is one of 250 press correspondents admitted and reports for Scandinavian newspapers on the proceedings conducted by the Allies. In keeping with regulations, he wears a Norwegian uniform with the band “War Correspondent” on his left sleeve.

While Brandt would rather have seen German anti-Nazis on the side of the accusers, he hails the trials as decisive progress in the development of international justice. The proceedings unveil the barely endurable extent of German crimes, most of all the genocide against the Jews of Europe.

Impressions of occupied Germany

In late 1945, Willy Brandt took advantage of a two-week pause in the Nuremberg Trials to spend Christmas with his mother in Lübeck. The 32-year-old celebrated New Year’s Eve and Day with his girlfriend Rut Bergaust in Stockholm.

In early January 1946, he returns to Germany for another eight weeks. At this time, Brandt is interested not only in the court proceedings but also in the current living conditions in the country. To this end the journalist travels from Nuremberg to cities and regions in the American occupation zone. Subsequently, the impressions that he gains are channelled into press articles and form the basis for his book “Criminals and Other Germans.”

First meeting with Kurt Schumacher

On 26 February 1946, a conference of SPD delegates from the American and French occupation zones takes place in Offenbach. Willy Brandt witnesses the meeting as a reporter for the Norwegian workers’ press services. On the fringes of the event, he introduces himself to Kurt Schumacher, leader of the SPD in the western zones. It is their first meeting.

As soon as autumn 1945 and early 1946, Brandt has expressed in letters to Schumacher his desire to return to Germany and make his contribution to the reorganisation of the SPD. However, at their conversation in Offenbach, Brandt has the impression that the leadership of the party is not interested in his participation anytime soon. On 5 March 1945, he returns to Oslo.

Against the forced unification of the KPD and SPD

At a party conference in the East Sector of Berlin on 21/22 April 1946, the KPD and SPD in the Soviet Occupation Zone (SBZ) merge into the Socialist Unity Party of Germany (SED). It is the result of massive Soviet pressure. In complete agreement with Kurt Schumacher’s leadership of the western zone SPD, Willy Brandt emphatically rejects the new party.

In a letter from Oslo dated 30 April 1946 to his old SAPD companion Jacob Walcher, he denounces the “undemocratic means” and “violent methods” used at the founding of the SED. The 32-year-old sees the forced unification as a facilitator of the tendency toward a partition of Germany. The paths of the former friends finally separate. Walcher becomes a member of the SED while Brandt clearly aligns himself with the SPD.

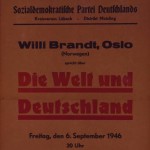

At the SPD party convention in Hannover

From 9 until 11 May 1946, Willy Brandt participates, as a delegate of the national group in Sweden and concurrently as journalist for several Scandinavian newspapers, in the first post-war party convention of the SPD in Hannover. However, only Kurt Heinig is allowed to speak for the social democrats in Swedish exile. His renewed efforts to circulate personal slanders against Brandt and to denigrate him to the party leadership has an effect. The 32-year-old realises that several leading members of the SPD encounter him with suspicion.

Brandt receives vastly differing signals on prospects for employment in Germany. Fritz Heine, a member of the executive committee, would like to keep him on as liaison in Scandinavia. The newly elected party chairman, Kurt Schumacher, advises him instead to return home soon and expresses the desire to hire him to establish a press service for the party in the Ruhr District. Finally, Brandt follows a third suggestion and applies for the position of executive editor with the German General News Agency (DANA) in Bad Nauheim. Before his return to Norway, he once again travels in mid-May 1946 for one week as a press correspondent to the Nuremberg War Crimes Trials and subsequently makes a stop in Lübeck.

The book “Criminals and Other Germans”

Willy Brandt’s book “Forbrytere og andre tyskere” (“Criminals and Other Germans”) appears in Oslo in June 1946. The report from Germany is based on impressions which he has gained in the previous months at the Nuremberg War Crimes Trials and on trips throughout the country.

Brandt opposes anew the thesis of collective guilt whereby all Germans are Nazis and criminals. But he does emphasise that every German must face the political responsibility for all of the crimes of the NS regime. Brandt also describes at length the difficult living conditions of the people, especially in the cities heavily damaged by the war.

Later opponents will unjustly accuse him of having equated Germans and criminals in the title of the book. The work does not appear in a German-language edition until 2007.

Uncertain professional future

In summer 1946, Willy Brandt is still undecided as to where and at what he wants to work. In Germany, he apparently has more options. Besides his application to the news agency DANA in Bad Nauheim, the 32-year-old is also being considered for the post of editor-in-chief of the German Press Service (DPD) in Hamburg.

In mid-August 1946, Brandt travels once more to Germany to introduce himself personally to the American and British occupation authorities who are responsible for the two news agencies. But he does not particularly care for the two jobs.

Mayor in Lübeck?

After an additional side-trip to the Nuremberg War Crimes Trials, Willy Brandt returns once again to Lübeck in early September 1946. Together with Annedore Leber, the widow of Julius Leber, he supports the SPD with an appearance in the municipal election campaign.

Lübeck’s social democrats want to win Brandt for their political work as a successor to Leber in the Hanseatic city. A suggestion that he run for mayor of Lübeck even comes from Theodor Steltzer, whom he came to know as a conservative opponent of Hitler in Stockholm exile and who is now senior president of the province of Schleswig-Holstein and a CDU member. Brandt reacts sceptically but delays making his decision.

Job offer for Paris

In October 1946, a completely new professional perspective is offered to Willy Brandt. His friend of many years, Norway’s foreign minister, Halvard Lange, offers him the post of press attaché at the Norwegian embassy in Paris.

Brandt is torn between two choices as is shown in a letter to Stefan Szende. For he had in the meantime made the difficult decision to go to Lübeck. On the one hand, the assignment in the French capital excites the 32-year-old, because it could be a fine starting point for a later career in international organisations. On the other hand, he would have to definitively relinquish any further participation in German politics.

Brandt is already inclined to accept the Paris post when Lange unexpectedly asks him if he wants to become the press attaché at the Norwegian Military Mission in Berlin.

Decision for Berlin

Willy Brandt has accepted the offer by foreign minister Halvard Lange and goes to the Norwegian military mission in Berlin as its press attaché. He has to commit for one year and can then decide whether he wants to remain in Germany or embark on an international path.

In an open letter dated 1 November 1946 to political and personal friends, the German-Norwegian solicits understanding for his decision. Decisive for him is the question of where he, as a “European, democratic socialist,” can best serve “the European renaissance and with that German democracy.” Brandt assures those citizens of Lübeck who had counted on his return that he “will never forget and certainly never abandon” the old Hanseatic city.

Test of patience in Copenhagen

Willy Brandt and his partner, Rut Bergaust, spend Christmas 1946 in Copenhagen. There he is waiting for the official papers which will allow his return to Germany and assumption of the post at the Norwegian military mission in Berlin. However, their delivery is delayed.

On top of that, Rut has to travel to Norway after learning that her husband, Ole Bergaust, died of tuberculosis on 29 December 1946. Lonely and suffering from a cold, Willy sits in a hotel and becomes more nervous every day until the necessary travel documents finally arrive after more than two weeks. In mid-January 1947, Brandt can travel by train by way of Hannover to Berlin.