School of the North – Scandinavian imprintings 1933–1946

© Archiv der sozialen Demokratie, Bonn

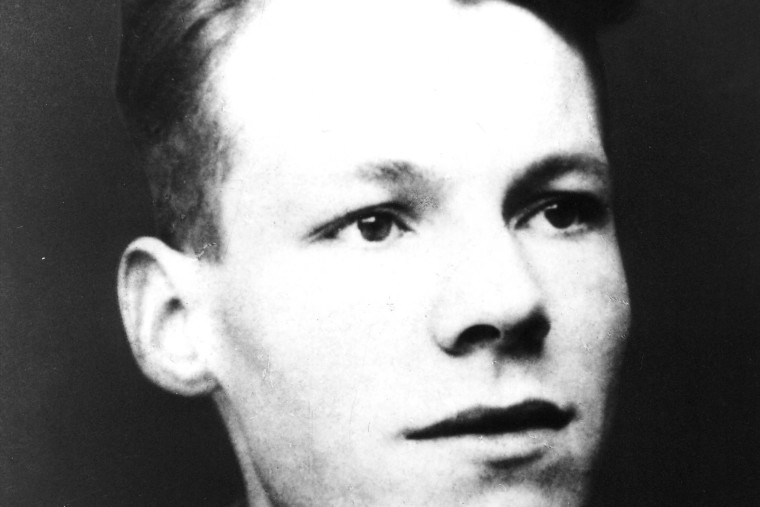

In 1933, Willy Brandt finds asylum in Norway from persecution by the Nazi regime. The Norwegian Workers’ Party DNA, in which he also becomes politically involved, supports him. Norway becomes his second homeland. After the German occupation and his escape to Sweden, Brandt obtains Norwegian citizenship in 1940. Until the end of World War II, he campaigns passionately for the Norwegian’s struggle for freedom. Strongly influenced by the Nordic democracies, Brandt is transformed from a left-wing revolutionary socialist into a social democrat.

Start-up aid from the Norwegian Workers’ Party DNA

At his arrival in Oslo in early April 1933, Willy Brandt, who is there to establish a foreign base of operations for the Socialist Workers’ Party of Germany (SAPD) in its resistance against the Nazi regime, is able to rely on various types of aid from the Norwegian Workers’ Party DNA. Both parties are members of the “Internationale Arbeitsgemeinschaft (IAG)” (“International Alliance”), a very small umbrella group of revolutionary socialist organisations.

Through mediation by Finn Moe, the foreign affairs editor of DNA’s party organ “Arbeiderbladet,” the new arrival comes immediately into contact with its editor-in-chief, Martin Tranmæl, so that after only a few weeks Brandt can publish his first articles in Norwegian. Since he learns the language quickly, he is soon able to work as a journalist and to hold lectures. For the most part, his contributions focus on the question of how Hitler was able to seize power and what fault the German workers’ movement has in this.

At the very beginning, the 19-year-old also becomes acquainted with the DNA chairman, Oscar Torp, who helps him obtain a place to live, financial support and a work permit. In the months and years to come, Torp will intervene successfully at the Norwegian Ministry of Justice several times to guarantee that Brandt’s limited residence permit is repeatedly extended and that he is not deported to Germany.

Struggle over the course of the DNA

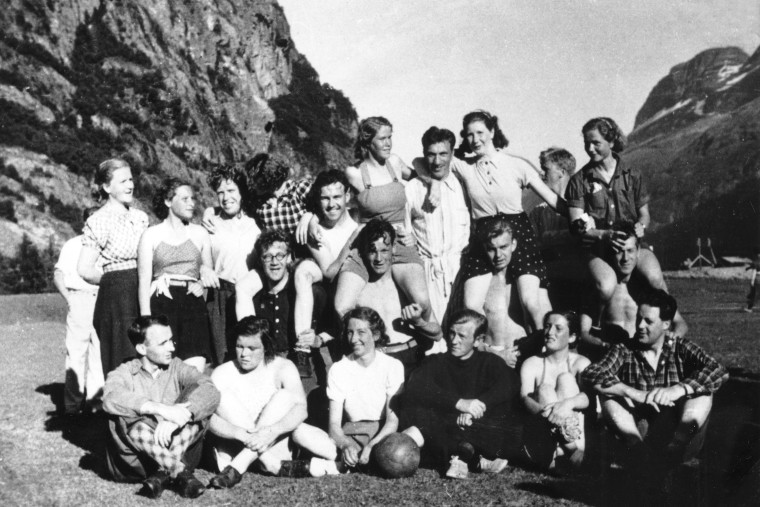

In close consultation with Jacob Walcher, chief of the foreign headquarters of the SAPD in Paris, Willy Brandt is involved from the beginning in the Norwegian workers’ movement. He becomes a member of the DNA youth organisation, Arbeidernes Ungdomsfylking (AUF). According to Walcher’s adventurous plan, the young German is to try and convince the Norwegian Workers’ Party, with the help of its left wing, to adopt a revolutionary course of action.

In order to strengthen the opponents of the moderate DNA leaders, in autumn 1933 Brandt secretly joins the Marxist intellectual organisation, “Mot Dag” (“Toward the Day”). At the head of this elite group, which was already excluded from the DNA in 1925, is the former communist, Erling Falk. Strong opposition within the party and his association with “Mot Dag,” to whose leading circle he belongs beginning in 1934, result in fierce conflicts for Willy Brandt with the DNA chairman, Oscar Torp. For this reason, the party periodically withdraws its material support for him.

Part of the Norwegian workers’ movement

Not until spring of 1935 does his relationship with the DNA become less tense. Counter to the desire of his SAPD comrades in Paris, Brandt separates himself from “Mot Dag.” In addition, the 22-year-old makes positive comments about the Norwegian Workers’ Party’s formation of a government in March 1935, even though it does not wish to incite a revolution, but rather carries out reform policies in the framework of parliamentary democracy.

Gradually Brandt begins to change his thinking and to distance himself from the revolutionary rhetoric of the SAPD. A major role in this change is his experience with the DNA leadership which, despite all of his factionalism, repeatedly demonstrates tolerance toward and solidarity with him. Most of all, their reform policies are successful, which impresses Willy Brandt. In Norway, fascists as well as communists are relegated to the political fringes. The DNA has turned into a mainstream party and is an electable choice for any farmer, fisher or civil servant.

In 1939, after some initial scepticism, Brandt endorses the new reform-oriented party programme which strongly influences his political thinking. By this time he has long been fully integrated in the Norwegian workers’ movement. Norway, whose citizenship he applies for after his deprivation of citizenship by German authorities in 1938, has become his second homeland.

Exile in Stockholm

The occupation of Norway by German troops in April 1940 forces Willy Brandt to leave Oslo on the spur of the moment. So as not to fall into the hands of the Gestapo, he puts on a friend’s Norwegian uniform and allows himself be taken prisoner by the German Wehrmacht. After his brief time as a prisoner of war, he flees to Sweden. He obtains a Norwegian passport in Stockholm, where he arrives in July 1940.

Belonging to the Norwegian exile community, Brandt devotes his efforts as a journalist and publicist to the liberation of Norway. Together with the Swede, Olov Jansson, he operates a “Swedish-Norwegian Press Office.” In addition to this, he is a co-worker for the resistance paper “Håndslag” (“Handshake”) which is published by the Swedish writer, Eyvind Johnson. This newspaper is smuggled across the border and plays an important role in bolstering the morale of the Norwegians. Brandt also writes several books about his fellow Norwegians’ struggle for freedom. He also reports for an US news agency about the war in Europe and Nazi crimes in the territories occupied by the Germans.

Beyond these activities, his intensive discussions with democratic socialists from 14 countries in the so-called “Kleine Internationale” “(“Little International”) in Stockholm are characteristic for him as well as his contacts with the Social Democratic Party of Sweden. Brandt admires Swedish social democracy which in his eyes acts in an undogmatic, freedom-loving, popular and power-conscious manner. In particular, it is the Swedish concept of the “Volksheim” (“people’s home”), of the democratic and reformist “social welfare state,” which fascinates him and which he will later pursue as a social democrat in Berlin and in Bonn.

Scandinavian correspondent in post-war Germany

After the end of World War II in Europe in May 1945, Willy Brandt frequently commutes between Oslo and Stockholm. In November 1945, he again travels to Germany. Until spring 1946, he reports from Nuremberg for the Scandinavian worker’s press on the trial against the major war criminals of the “Third Reich.” The impressions of his four-month stay in Germany are treated in his book “Forbrytere og Andre Tyskere”(“Criminals and Other Germans”), which appears in Norway and Sweden in 1946.

With this work he wants to make it clear to his Scandinavian public that not all Germans can be branded collectively as Nazi criminals. At the same time, Brandt stresses that each German must face up to the political responsibility for the genocide committed by the Nazi regime.

References to literature:

Willy Brandt – Berliner Ausgabe, Bd. 1: Hitler ist nicht Deutschland. Jugend in Lübeck – Exil in Norwegen 1928–1940, bearb. von Einhart Lorenz, Bonn 2002.

Willy Brandt – Berliner Ausgabe, Bd. 2: Hitler ist nicht Deutschland. Zwei Vaterländer. Deutsch-Norweger im schwedischen Exil – Rückkehr nach Deutschland 1940–1947, bearb. von Einhart Lorenz, Bonn 2000.

Willy Brandt: Links und frei. Mein Weg 1930–1950, Hamburg 1982 (Neuauflage 2012).

Willy Brandt: Verbrecher und andere Deutsche. Ein Bericht aus Deutschland 1946, bearb. von Einhart Lorenz, Bonn 2007 (Bd. 1 der Willy-Brandt-Dokumente).